Betraying Your Church—And Your Party

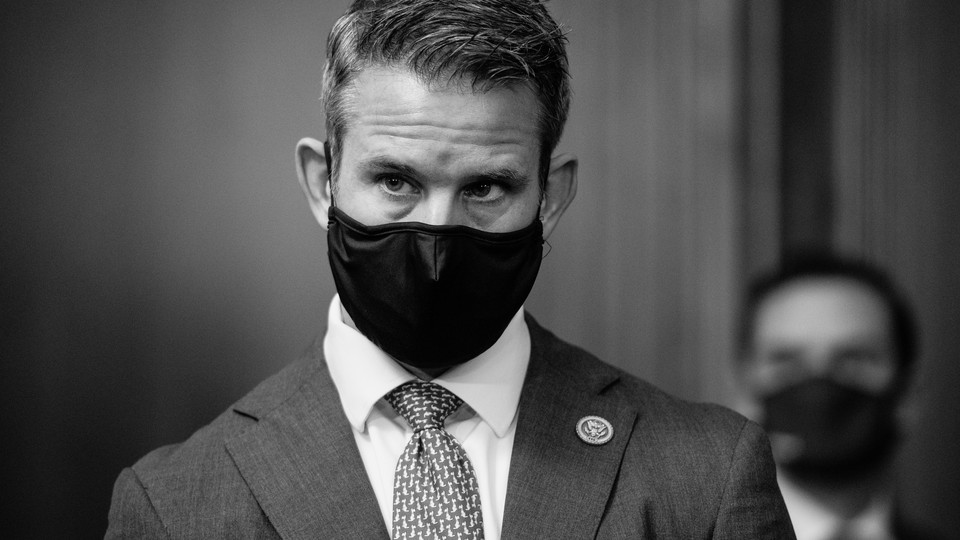

How Representative Adam Kinzinger, an evangelical Republican, decided to vote for impeachment—and start calling out his church

The letter writer’s message was clear: Representative Adam Kinzinger is doing the devil’s work, and he is possessed by demons. It’s not hard to guess why Kinzinger would receive such a note. He was one of 10 Republican members of Congress who defied their party and voted to impeach President Donald Trump for inciting the January 6 insurrection at the Capitol. Kinzinger knew most Republicans in his solidly conservative district would not agree with him. But the choice was easy: As someone who identifies as a born-again Christian, he believes he has to tell the truth. What has been painful, though, is seeing how many people who share his faith have chosen to support Trump at all costs, fervently declaring that the election was stolen. The person who sent that letter—by registered mail, to be extra sure he got it—was a member of Kinzinger’s family. “The devil’s ultimate trick for Christianity … is embarrassing the church,” he told me and a small group of other reporters this week. “And I feel it’s been successful.”

Kinzinger is not a pastor or a theologian. He knows his job as a representative is not to preach the gospel but to represent his constituents and vote on legislation. When he’s dead, however, it won’t matter how many elections he won, or how low America’s tax rates are. The Lord has been speaking to him about his role as a Christian in politics, he said, and how he can reach people who are thinking about their eternal life. He has concluded that his faith and his party have been poisoned by the same conspiracy theories and lies, culminating in the falsehood that the election was stolen. When you look at “the reputation of Christianity today versus five years ago, I feel very comfortable saying it’s a lot worse,” he said. “Boy, I think we have lost a lot of moral authority.”

But people like Kinzinger have not been the ones shaping the reputation of Christianity in America over the past four years. Trump’s supporters have. Even after everything that’s happened—Trump’s attempt to overturn the election, his cheerleading for the attack on the Capitol—some influential evangelical leaders are still defending the president: “Shame, shame,” Franklin Graham, the evangelist and son of the famous pastor Billy Graham, wrote about the 10 Republicans who voted for impeachment. “It makes you wonder what the 30 pieces of silver were that Speaker Pelosi promised for this betrayal.” In the metaphor, the Republican dissidents are cast as Judas, who is said to have betrayed Jesus in exchange for 30 coins. Trump plays the role of Christ.

Looking to political personalities rather than Jesus for salvation is the worst kind of mistake a Christian can make, Kinzinger said. “There are many people that have made America their god, that have made the economy their god, that have made Donald Trump their god, and that have made their political identity their god.” The problems that led to the January 6 insurrection are not just political. They’re cultural. Roughly half of Protestant pastors said they regularly hear people promote conspiracy theories in their churches, a recent survey by the Southern Baptist firm LifeWay Research found. “I believe there is a huge burden now on Christian leaders, especially those who entertained the conspiracies, to lead the flock back into the truth,” Kinzinger tweeted on January 12.

As a kid growing up in a Baptist church, Kinzinger was “constantly in Sunday school,” and his dad ran ministries that served the hungry and the homeless. Politics was a natural part of this world: Kinzinger attended meetings of the Christian Coalition, the evangelical advocacy group, and learned about the importance of advocating against abortion. But over time, as the tie between Republican politics and evangelical Christianity got tighter, he began to see conservative policies used as a litmus test for whether people were true Christians. Kinzinger believed that Republican ideas were superior to Democratic ones—he first got elected to the county board in McLean County, Illinois, as a 20-year-old local-government advocate. But it bothered him that many Republicans viewed their political opponents as evil enemies, rather than people who might even share their faith. “We get wrapped up in thinking that every little political victory that we do [that] has an impact on an election is actually fighting for God and the truth,” he said.

Kinzinger first got elected to Congress under Barack Obama, and over the past decade, he has watched his party transform. “No longer does policy actually matter. It’s all about: Do you support Donald Trump, or don’t you? Do you want to own the left, or don’t you?” he said. Although he stated publicly that he wouldn’t vote for Trump in 2016, he did vote for the president in 2020, citing a desire to build on the administration’s policy successes. Unlike some Republicans, he has not spent the past four years on the front lines of the Never Trump resistance; he generally supported Trump’s agenda in Congress, voting in line with the president’s goals roughly 90 percent of the time. But unlike other members of the GOP, Kinzinger was unwilling to keep fighting for Trump after it was clear that he had lost the election. “I’m embarrassed by some of my Republican colleagues on the floor. They have defaulted to political points for fame and have failed to rise to this moment,” he tweeted on January 6. He later joined Democrats to encourage Vice President Mike Pence to invoke the Twenty-Fifth Amendment and remove Trump from office.

Dissent is costly for Republicans and Christians alike. Kinzinger said he’s been getting nonstop hate mail since his impeachment vote, calling him a traitor and a RINO, or Republican In Name Only. He’ll likely face a primary fight in 2022. But in the long run, quietly going along with the claim that the 2020 election was stolen could be costly too. Only a third of Millennial voters identify as or lean Republican. Among this age group, more people are nonreligious than part of any single faith group, including evangelical Christianity. It bothers Kinzinger that his party doesn’t seem to care that America’s 20- and 30-somethings are widely disillusioned with the GOP. And it bothers him that some evangelicals’ obsession with Trump may make it harder for young people to find Christ. “That’s a pretty terminal demographic to lose,” he said. Over the past few weeks, he’s been talking with other Christians in the House about what it means to act without fear—including the fear of losing elections. “Our time on earth is not going to be that long compared to eternity,” he said.

On January 6, as an armed mob invaded the House of Representatives, Kinzinger said he could feel a darkness descend over the Capitol. One of his friends in Congress, the Oklahoma Republican Markwayne Mullin, heard the same thing from members of the Capitol Police. Kinzinger doesn’t doubt that the devil is at work in American politics. He just suspects that the enemy might be lurking in his own house.