The past 11 months have been a crash course in a million concepts that you probably wish you knew a whole lot less about. Particle filtration. Ventilation. Epidemiological variables. And, perhaps above all else, interdependence. In forming quarantine bubbles, in donning protective gear just to buy groceries, in boiling our days down to only our most essential interactions, people around the world have been shown exactly how linked their lives and health are. Now, as COVID-19 vaccines rewrite the rules of pandemic life once more, we are due for a new lesson in how each person’s well-being is inextricably tangled with others’.

This odd (and hopefully brief) chapter in which some Americans are fully vaccinated, but not enough of us to shield the wider population against the coronavirus’s spread, brings with it a whole new set of practical and ethical questions. If I’m vaccinated, can I travel freely? Can two vaccinated people from different households eat lunch together? If your parents are vaccinated but you’re not, can you see them inside? What if only one of them got both shots? What if one of them is a nurse on a COVID-19 ward?

After asking four experts what the vaccinated can do in as many ways as I could come up with, I’m sorry to report that there are no one-size-fits-all guides to what new freedoms the newly vaccinated should enjoy. Still, there is one principle—if not a black-and-white rule—that can help both the vaccinated and the unvaccinated navigate our once again unfamiliar world: When deciding what you can and can’t do, you should think less about your own vaccination status, and more about whether your neighbors, family, grocery clerks, delivery drivers, and friends are still vulnerable to the virus.

The COVID-19 vaccines are fantastic. The shots that are currently available are tremendously effective at protecting the people who get them from severe illness, hospitalization, and death—all the things we want to avoid if we have any hope of fully reopening society. Even so, advice on what people can do once vaccinated gets complicated. Those who are vaccinated can still be infected by, and test positive for, SARS-CoV-2; they’re just way, way less likely to get sick as a result. The sticky element is whether not-sick-but-still-infected vaccinated people can spread the virus to others and get them sick. So far, the early data have been promising, showing that the vaccines stop at least some transmission, but the matter is not scientifically settled.

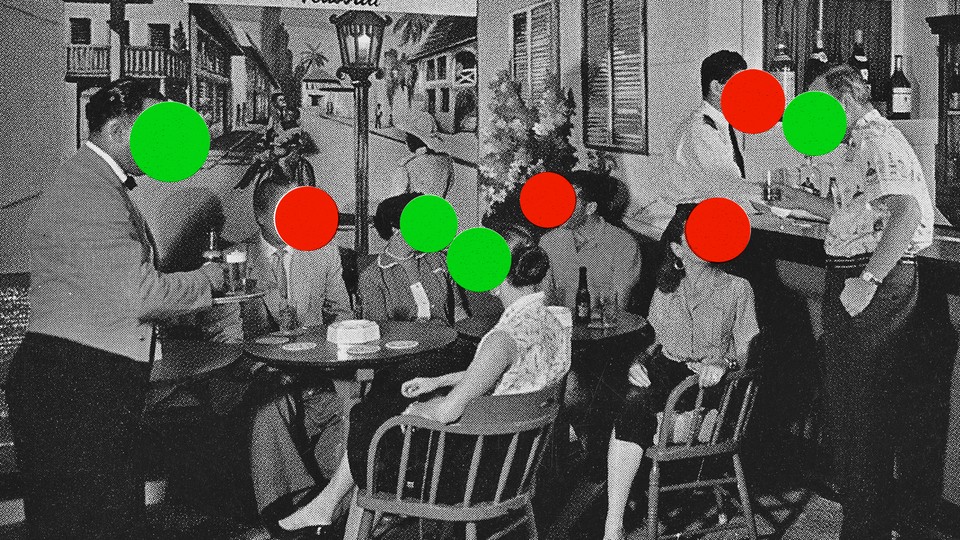

This leaves us in an awkward situation. Getting vaccinated means that your choices no longer endanger you much, but they still might make you a risk to everyone else. To put this in more concrete terms: If a vaccinated person goes out to eat, they can’t yet be sure that they’re not carrying the virus and spreading it to their unvaccinated fellow diners and the restaurant staff, or that they won’t pick up the virus at the restaurant and bring it home to their unvaccinated family.

So, first, a very broad guideline for navigating a world in which vaccinations are rising and infections are dropping: Whether you’re vaccinated or not, how much you can safely branch out in your activities and social life depends on the baseline level of virus in your community. You can imagine that, in pandemic life, each of us has been dealt a certain number of risk points that we can spend on seeing friends outside, going to work, sending the kids to day care, and so on. If you or someone you live with is especially vulnerable to the virus, you might choose to spend fewer points by getting groceries delivered; if you live alone in an area where very few people are sick, you might choose to spend more points by forming a bubble with friends. The vaccine delivers you a huge number of bonus points, if you’re lucky enough to get one. And when spread of the virus is low, everyone gets more points.

Saskia Popescu, an infectious-disease epidemiologist at George Mason University, told me that everyone, vaccinated or not, should try to keep track of three metrics in your area: The number of new daily cases per 100,000 people, the rate at which people transmit the virus to one another, and the rate at which people test positive for the virus. Popescu said that there are no magic numbers that would immediately bring the country back to pre-COVID life, but she’ll feel better about reopening when we hit daily case rates of just one to two per 100,000, transmission rates of .5 or less, and test-positivity rates at or below 2 percent. (As of last week, no U.S. state had reached the trifecta, and the country as a whole is still far from it.) Many local public-health departments regularly provide these numbers.

You might be tempted to factor vaccination rates into your safety equation too, but Whitney Robinson, an epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina, told me that those numbers shouldn’t be anyone’s main safety indicator. That’s because vaccine distribution so far has been concentrated in particular social networks (for instance, health-care workers) and demographic groups (notably the white and wealthy), so an entire community won’t necessarily reap the benefits that a local vaccination rate of 15, or even 50, percent might imply.

Knowing the overall risk of infection in your area is at least a first step toward making better decisions about whether you should host that birthday party or take Grandpa out to lunch. Even for people who are vaccinated, all of the public-health experts I spoke with emphasized, it’s still important to not throw caution to the wind. If vaccinated people flock to indoor restaurants or go unmasked in a crowd, they’re not just risking infecting others if they can indeed spread the virus, Popescu said. They’re contributing to a sense that life as we knew it before March 2020 is back, despite the fact that more than 65,000 people are still contracting the virus each day. Simply returning to our old habits would be deadly.

That doesn’t mean that any loosening up is off the table for the vaccinated. Far from it—plenty of public-health experts have argued that vaccinated people safely seeing relatives or returning to the office can benefit everyone, because seeing how much the shot improves life will persuade more people to take it. Downplaying the vaccines’ success could discourage people from getting them, because if it won’t change their lives, they have no incentive.

The best way forward for us all is for vaccinated people to spend their extra risk points in ways that don’t put unvaccinated people in danger. As you consider whether you should do things that you wouldn’t have done before the vaccine, think creatively about how you can make those things safer for everyone involved. “Grandparents really want to be able to go hug their grandchildren,” Tara Kirk Sell, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, told me. “I don’t have a problem with that.” But consider asking Grandma and Grandpa to wear masks during that hug, or meet you outside, or avoid sleeping over. Throughout the pandemic, we’ve developed an arsenal of strategies to make particular settings and activities safer. The vaccine is an extra-strong weapon against transmission that some people can deploy, but that doesn’t mean they need to discard all of the other ones to use it.

How many of those methods you choose should depend on how many vulnerable people you regularly come into contact with. A vaccinated oncologist who lives with her immunocompromised sister is going to behave differently from a vaccinated retiree who lives alone. That said, there are plenty of settings, such as restaurants and stores, where you don’t know or can’t control how many vulnerable people are around you. For that reason, small private gatherings where you can adjust your anti-spread tactics to accommodate everyone’s risk factors are a safer first step toward normalcy than activities such as concerts, indoor dining, or big weddings. Travel in small groups might be a nearer goal, too: Popescu said she hopes that by the end of the year, she can take a vacation in another state with her husband without worrying that she’s “being a bad steward of public health.”

Playing it safe, even as you loosen up a little, is the best way to ensure that someday, you will again live in a world with bars and birthday parties and movie theaters. It’s also the best way to keep yourself from getting sick with COVID-19 in the future—regardless of whether you’re already vaccinated. No one knows exactly how long you’ll be protected against serious illness if you get a vaccine (or were previously infected), simply because no one has been vaccinated for more than seven months yet. Given what we do know so far, the most likely way for a vaccinated person to get seriously ill from the coronavirus would be if they encounter a variant that the vaccine they received doesn’t effectively protect against. Such variants are much more likely to emerge if the virus is allowed to rage in particular places or groups before the overwhelming majority of the world’s people can be vaccinated.

As Gregg Gonsalves, an epidemiologist at the Yale School of Public Health, put it, “In the context of epidemiology, we’re all in the same boat.”

The Atlantic’s COVID-19 coverage is supported by grants from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.