Impeachment Poses One Question

Much of the legal wrangling serves to obscure the central matter before the Senate.

One casualty of a moment in American life when politics seems to pervade everything is an inability by many prominent people to tease apart what is and is not a matter of politics.

The second impeachment trial of former President Donald Trump, which gets under way today, offers several prime examples. As the refrain went during Trump’s first impeachment, in 2019 and early 2020, the impeachment process is political and not legal, even though it resembles a criminal trial. Yet in both the Democratic House managers’ case for prosecution and (more seriously) the defense brief from Trump’s attorneys, there is a confusion between matters that are appropriately legal or factual, and those that are political.

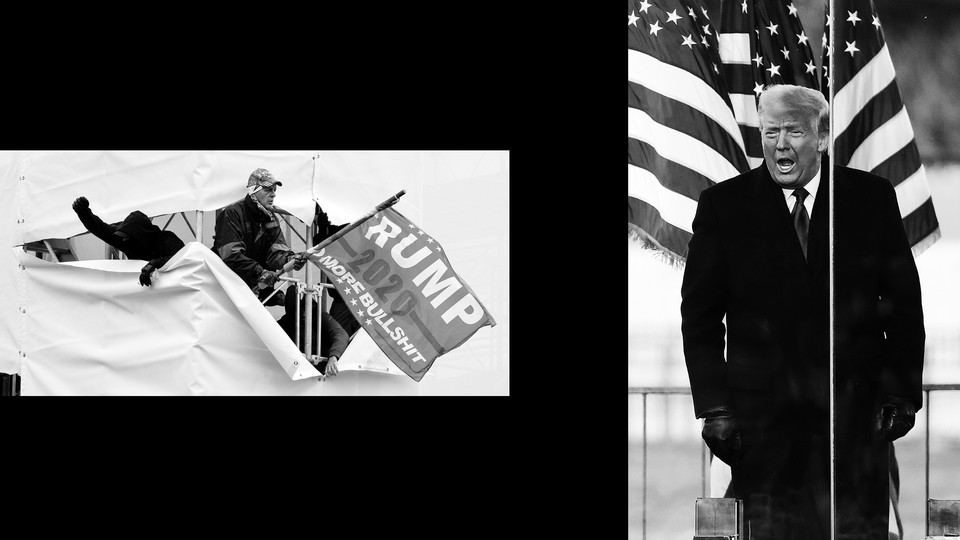

The basic misdeed for which the House impeached Trump is simple enough to understand in plain English: He tried to overturn the 2020 presidential election, by pressuring various officials to change the results and then by encouraging a mob to storm the U.S. Capitol to stop the certification of his defeat. The House’s single article of impeachment against Trump, passed in January, and the House managers’ brief each land on “incitement” of both insurrection and violence as a term to describe Trump’s behavior after the election.

The term is both too narrow and too broad. It tries to reduce the matter down to a concise term that resembles a charge that one might hear in a court of law. (It is probably not a coincidence that all nine managers are trained lawyers.) In legalizing what is rightly a political matter, however, the managers inadvertently encouraged recourse to the legal definition of incitement, and in particular to the Supreme Court’s test for what constitutes the crime of incitement in Brandenburg v. Ohio, which, in the interest of protecting free speech, creates a difficult bar to surmount in a criminal court.

The decision to focus on an official-sounding but ultimately irrelevant (and even counterproductive) term has been a leitmotif of anti-Trump discourse over the past four years. The first and worst major case was the intense hermeneutics around whether the Trump campaign “colluded” with the Russian government (spoiler: yes), even though—as Special Counsel Robert Mueller was at pains to point out in his 2019 report, “collusion is not a specific offense or theory of liability found in the United States Code, nor is it a term of art in federal criminal law.” Other low points included quid pro quo and blackmail in the Ukraine scandal, both of which became subject to intense semantic fights that distracted from the basic fact that Trump had extorted Ukraine’s government to assist him in the election.

With any luck, incitement will be a last gasp of this pattern. The use of the term here is a problem because it creates an opening for one of two big, spurious arguments that the Trump defense team offers. First, it contends that none of Trump’s actions meets the legal standard for incitement laid out in Brandenburg, and therefore he “cannot be subject to conviction by the Senate under well-established First Amendment jurisprudence.”

Moreover, Trump’s lawyers argue, the Senate doesn’t have the jurisdiction to try the case, because Trump has already left office. This is a matter of robust legal discussion. Some experts, and Democrats, argue that the Senate can still convict Trump and bar him from future elected office. Others contend that because Trump has left office, the proceeding is moot. These legal questions are interesting, but also essentially academic. The Constitution gives Congress sole power of impeachment, which means that the Senate gets to decide whether it can try Trump. On January 26, the body voted on that question, and concluded that the trial was constitutional. (Also relevant: The House impeached Trump while he was still in office; the Senate is required to try impeachment cases, and it could have tried the case before Trump left office, except for the fact that the Republican leader, Mitch McConnell, didn’t want to.) The point is that impeachment is whatever Congress says it is—it’s a political question.

Meanwhile, Trump’s defense team mostly ignores and deflects the substantive point, which is that Trump tried to overturn the election. The lawyers attempt to dispense with the matter in a short “statement of facts” at the start of the brief. They focus narrowly on Trump’s speech on January 6, and contend that no one should have taken him seriously, he was speaking metaphorically, and anyway, law enforcement should have done its job better.

There are several problems with this. In one instance, they try to construe a factual matter as a political one. Trump spent weeks insisting that the election had been stolen—which, if true, might have justified his efforts to overturn it. The problem is that this was a lie. According to his lawyers, these statements “amount to no more than Mr. Trump’s advocating his position that he won the Presidential election in November 2020.”

This isn’t a matter, though, of espousing a political position, like supporting tax cuts or seeking to raise the minimum wage. As a matter of fact, Trump lost the election. By January 6, he had exhausted his remedies in court, every state had certified its count, and the Electoral College had voted. Even so, the president was frantically pressuring Vice President Mike Pence to throw the election to him and telling those in the crowd that they had to do something about it.

In another instance, Trump’s lawyers do the opposite, construing a political question as a legal one. On January 2, Trump called Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger and begged and threatened him to “find” enough votes to show that he had won reelection. “Examining the discussion with the Georgia secretary of state under the standard of ‘incitement,’ leads to the same conclusion as the January 6, 2021, statements of Mr. Trump,” the lawyers write. “There is nothing said by Mr.Trump that urges ‘use of force’ or ‘law violation’ directed to producing imminent lawless action.”

This objection is beside the point, though the Democratic brief invited it. The problem with Trump’s call to Raffensperger was not that it put him in breach of the Supreme Court’s incitement standard. The problem with the call was that he was trying to pressure an elected official into overturning an election.

Trump never grasped the weight that his words carry as president, as I have written previously. Despite his obsession with the trappings of the office, Trump continued to act blithely indifferent to the power his statements had, and the damage they could do. As a result, it might be impossible to convict Trump for inciting the insurrection in a court of law.

But the Senate is not a court of law. It need not matter to senators what Trump expected to happen, or even what a reasonable person in his position might have expected to happen. Fundamentally, senators must answer a political question: Can the nation afford to have a president who tries to overturn an election he lost?