One tribute to the late John Lewis began by noting his love of W. E. Henley’s “Invictus”; it seems to have been Nelson Mandela’s favorite too, as affirmed in Morgan Freeman’s reading of the poem.

During his bare half century on Earth, Henley was chronically ill with tuberculosis and other ailments, which led, among other things, to the amputation of his left leg. He died in 1903, at the beginning of a century during which that poem, timeless and universal in its sentiments, inspired these two men, of such different time, place, and predicament from his own.

Henley’s poem remains popular enough, although not so much as once it was. It can be found in quaint poetry books such as The Faber Popular Reciter, Kingsley Amis’s 1978 edited collection of old chestnuts, the kind of poetry that would make some sophisticates cringe, but that in the old days schoolchildren routinely memorized, to dredge such poems out—as Lewis and Mandela did—in moments of crisis.

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds and shall find me unafraid.

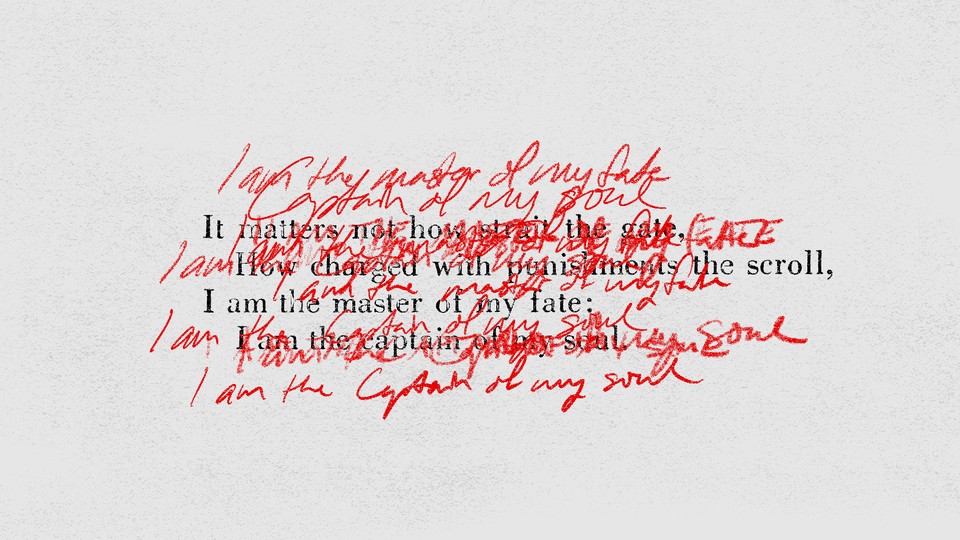

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll,

I am the master of my fate,

I am the captain of my soul.

Some poetry of this kind is written today, but not much—although Maya Angelou’s lines “You may trod me in the very dust / But still, like dust, I’ll rise” reverberate. But no matter: The storehouse of the past is amply stocked.

It is trite but true to say that we live in a time of acute anxiety—about the pandemic, social injustice, even the very foundations of our political order. We live, too, in a time when a posture of victimhood and one of its more dangerous variants, fragility, have become characteristic across the left and the right. Robust poems committed to memory can counteract the corrosive effects of self-pity. They can offer a different way of viewing the world, particularly to generations that did not suffer the buffetings of the early and mid-20th century, and are now bewildered by the calamities that seem to arise from nowhere, and leave them powerless.

During World War II, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill sought to raise each other’s spirits, and those of their people, by turning to some old favorites. When Roosevelt sent his defeated election opponent, Wendell Willkie, on a mission to embattled Britain in early 1941, he wrote out a verse from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow for him to give to the prime minister, saying to Churchill that the following lines from the last stanza of “The Building of the Ship” “applies to you people as it does to us”:

Sail on, O Ship of State!

Sail on, O Union, strong and great!

Humanity with all its fears,

With all the hopes of future years,

Is hanging breathless on thy fate!

Two months later, in April 1941, Churchill cited that verse while speaking to the British people, then turned to another 19th-century favorite, Arthur Clough’s “Say Not the Struggle Nought Availeth.” The British people were not alone, and as bad as matters looked following one defeat after another, there was hope for the future.

For while the tired waves, vainly breaking

Seem here no painful inch to gain,

Far back through creeks and inlets making,

Comes silent, flooding in, the main.

And not by eastern windows only,

When daylight comes, comes in the light,

In front the sun climbs slow, how slowly,

But westward, look, the land is bright.

Corny stuff, perhaps, but it came in handy. So too do lots of the old favorites. Rudyard Kipling is hardly in favor these days, but can one really quarrel with most, if not all of the sentiments in “If—”?

If you can force your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: ‘Hold on!’

The crying need of our time is for resilience, the ability not only to endure adversity and stress, but to recover our equanimity and even be strengthened by the ordeal. When Edna St. Vincent Millay declared:

My candle burns at both ends;

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends—

It gives a lovely light!

She was not feeling sorry for herself at the approach of dawn.

To add to the social and political turmoil of the moment, the anger and the fears, come now sheer weariness. As the shutdowns of the coronavirus continue, we all tire of Zoom calls, Netflix bingeing, and even, perhaps, attempts to tackle once again War and Peace or Moby-Dick. Perhaps, then, it is not a bad time to turn to poetry—and particularly to give those children who will have to go to school online in the fall and are driving their parents to the edge some valuable educational successes. Get them to memorize some poems and declaim them, then talk about what they mean. And do not shrink from giving them Walt Whitman’s “O Captain! My Captain!” to know what it is to lose a great leader, or W. B. Yeats’s “The Second Coming,” at a time when it often seems that “The best lack all conviction, while the worst / Are full of passionate intensity.”

It almost does not matter which poems they learn: You can be quite sure that the powerful ones will stick. Emily Dickinson was right:

The Props assist the House

Until the House is built

And then the Props withdraw

And adequate, erect,

The House support itself

And cease to recollect

The Auger and the Carpenter –

Just such a retrospect

Hath the perfected Life –

A past of Plank and Nail

And slowness – then the Scaffolds drop

Affirming it a Soul –

Poems such as “Invictus” can be that kind of scaffold. And the declaiming children too, like Lewis or Mandela, may find that in a time of need—maybe this time of need, maybe worse ahead—verse can help school souls that are, in fact, unconquerable.