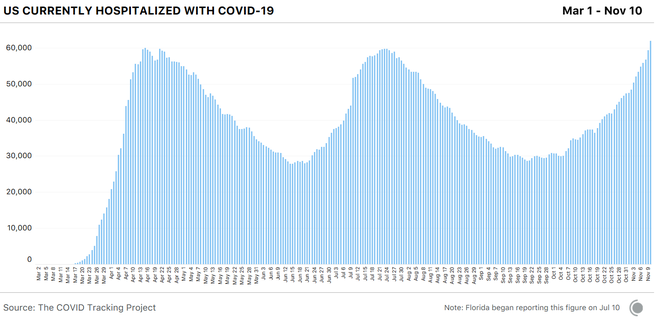

The United States is experiencing an unprecedented surge of hospitalizations across the country. Today, states reported that 61,964 people were hospitalized with COVID-19, more than at any other time in the pandemic. For context, there are now 40 percent more people hospitalized with COVID-19 than there were two weeks ago.

Seventeen states are at their current peaks for hospitalizations today. According to local news reports, hospitals are already on the brink of being overwhelmed in Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, North Dakota, Texas, Utah, and Wisconsin, and officials in many other states warn that their health-care systems will be dangerously stressed if cases continue to rise.

The new hospitalization record underscores that we’ve entered the worst period for the pandemic since the original outbreak in the Northeast. Although the number of detected cases was much lower back then because of test shortages, the large number of hospitalizations (and deaths) indicates that there were many more times the number of infections than our then-embryonic and broken testing system could confirm.

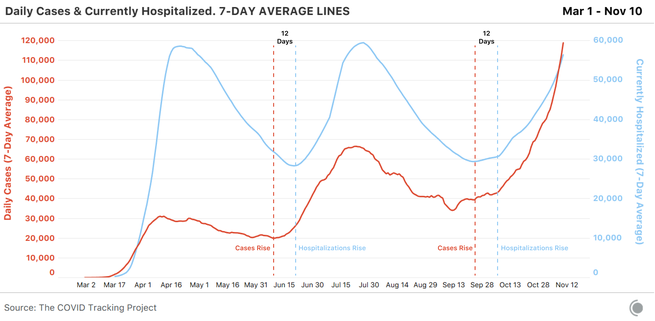

In the following months, some commentators, including government advisers, have played down the large case counts by saying tests were detecting people who weren’t actually sick—or if they were sick, only mildly sick. These hospitalization numbers prove that the current surge of COVID-19 cases is not merely the result of increased screening of asymptomatic people. Rather, the cases we’re detecting are a leading indicator that many people are seriously ill. Although case numbers are heavily influenced by the number of tests accessible in a particular area, hospitalizations are not.

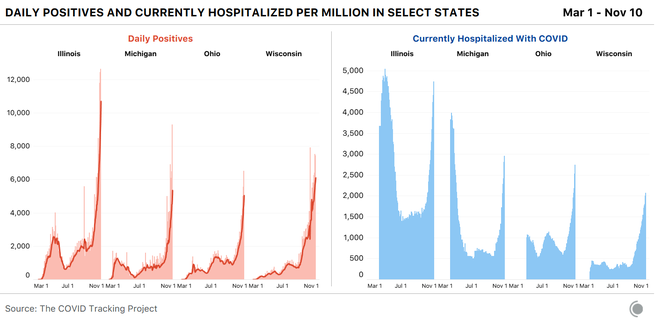

The burst of hospitalizations is primarily located in the Midwest, where cases began to rise weeks ago. We have seen no indication that there is an end in sight to the outbreaks in the region. The outbreaks in Illinois, Michigan, and Ohio began spiking more than three weeks after early outlier Wisconsin—and cases and hospitalizations in Wisconsin are still rising.

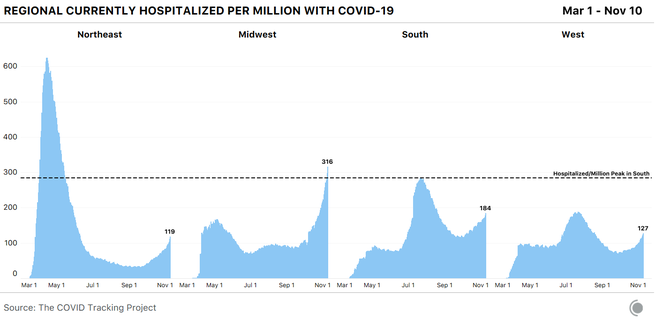

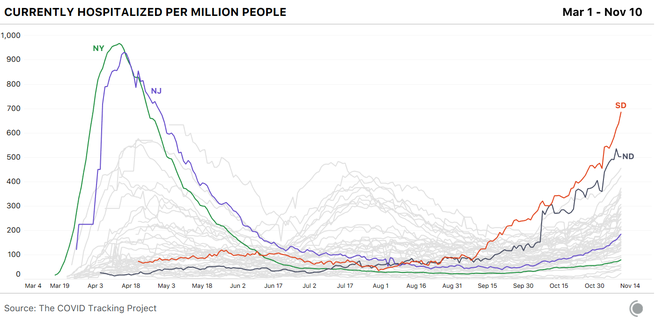

What we’re seeing in the Midwest could foreshadow what is in store for the rest of the nation. The current wave of COVID-19 infections stretches across the whole country, and hospitalizations are rising in every region. Per capita, hospitalizations in the Midwest have now outpaced the South’s peak over the summer.

Even the Midwest remains far short of the per-capita hospitalizations in the Northeast’s spring outbreaks, but some low-population Midwest states are posting alarming per-capita numbers. And as noted above, we may have a long way to go before we see these outbreaks peak.

In both North and South Dakota, more than 1 in 2,000 state residents are hospitalized with COVID-19 right now. Only New York and New Jersey have seen higher rates of hospitalizations per capita.

Treatments for COVID-19 have improved since the Northeast outbreak. The ratio of hospitalizations to deaths has fallen tremendously since the spring. But it is also true that wherever we see hospitalizations go up, deaths rise two to three weeks later. We’ve seen it happen in state after state, in region after region, and nationally as well.

Improved outcomes depend on maintaining the highest standard of care. With hospitalization numbers like these, it is not clear that health-care systems in all hard-hit areas will be able to maintain this standard. In North Dakota, so many health-care workers have contracted COVID-19 that the state is now putting asymptomatic—but still infectious—workers back into hospitals to care for patients. Another crucial difference from the spring: When the surge hit New York and New Jersey, thousands of medical workers flew in from all over the country to help treat patients. With so many states experiencing severe outbreaks at the same time, it could be harder to mobilize surges of frontline workers to areas where health-care systems are at risk of failure.

The COVID-19 fatality rate is not a constant that can be permanently improved by better knowledge of the disease and the availability of treatments alone. To recover, patients require attentive, informed, round-the-clock care. Although hospital systems have made emergency calls for federal staffing support, discharged seriously ill patients to die at home, and been forced to send patients to other regional hospitals, the United States has never experienced the kind of widespread health-care collapse and care rationing seen in other parts of the world in the spring.

Throughout the year, hospitals and health-care workers have issued warnings that if we do see hospitals overwhelmed, fatality rates will soar. As cases and hospitalizations continue to rise nationwide, we are poised to enter a new and possibly bleaker phase of the pandemic. We can only hope that if more state officials act quickly to establish effective mitigation measures, their effects will come in time to avoid the worst.

This post appears courtesy of The COVID Tracking Project.