The Paranoid Style in American Entertainment

How the mechanisms of reality TV taught us to trust no one

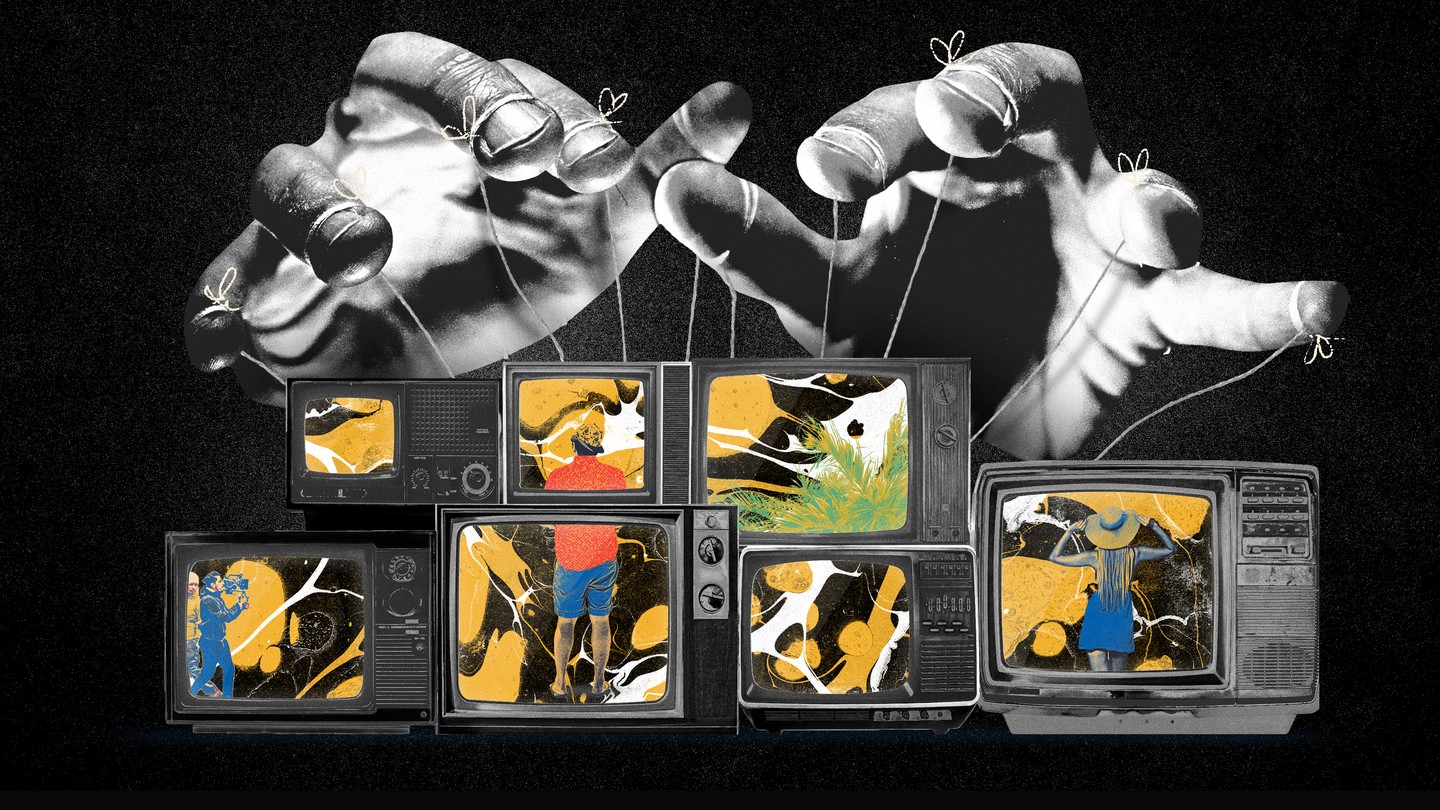

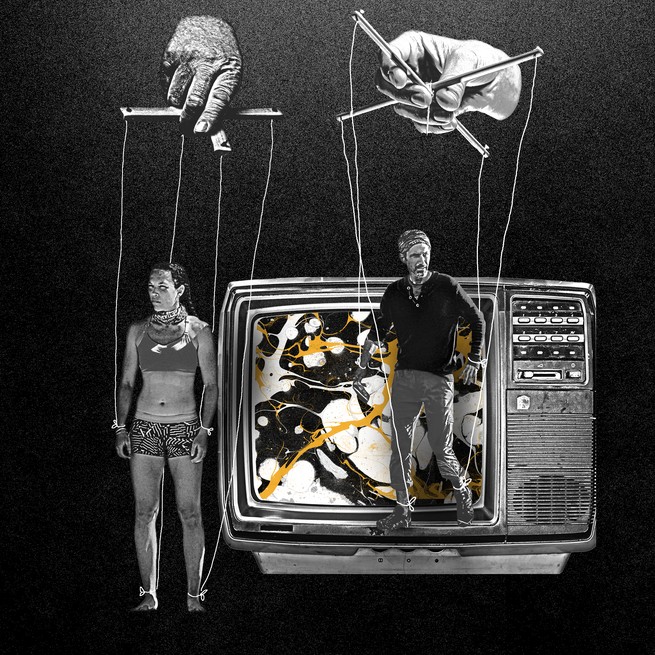

Photo-illustration by Max-o-matic

Last summer, BuzzFeed published an article detailing some of the betrayals that can occur when reality is reimagined as a genre of entertainment. Sourced from people who claimed to have inside knowledge of the workings of reality-TV shows, the piece included such resonant bummers as “Lifelines for Who Wants to Be a Millionaire can totally google the questions” and “Reactions on What Not to Wear aren’t genuine” and “Some couples on Divorce Court aren’t actually married.” The story joined years’ worth of similar articles (“Real or Fake? The Truth About Some of Your Favorite Reality TV Shows”; “Reality TV Hoaxes You Fell For”); that reality lacks realness was not at all, by mid-2019, a new revelation. BuzzFeed’s indictment was notable, however, for one of the headlines it ran under: “17 Secrets About Reality TV Shows That’ll Make You Question Everything.”

The hyperbole highlighted a truth. Reality TV really does encourage viewers to question everything—in part because it nullifies the distinction between fiction and fact. The genre involves real people, playing themselves on TV. It claims to be unscripted; in practice, it is thoroughly plotted and highly produced. It winks. But it also assumes that you, the audience, will wink back. Is The Bachelor real or fake? The answer is yes. How real are the Real Housewives? Real enough. The membranes are porous. Many Bachelor stars, allegedly looking for love, parlay the exposure the show gives them into gigs as Instagram influencers and professional “personalities.” Housewives alchemize their fame into $100 million cocktail brands. Viewers, for the most part, are privy to those transactions. They understand that reality, a postmodern genre in a post-truth culture, turns the logic of fictional entertainment on its head: It demands a willing suspension of belief.

The historian Richard Hofstadter titled his 1965 essay collection, an analysis of the cultural elements that convert suspicion into a way of life, The Paranoid Style in American Politics. The real subject of the book, however, is the American psyche—what mistrust, as an individual impulse, can look like at scale. Reality shows, ubiquitous in American culture not only on TV itself but also on Facebook and grocery-store magazine stands, quietly rationalize the kind of paranoia Hofstadter identified: They involve producers, unseen but omnipresent, who shape the course of human events. They suggest that suspicion might be the most rational option. The 2018 Reader’s Digest post “13 Secrets Reality TV Producers Won’t Tell You” is written in notably conspiratorial tones—and from the perspective of those producers. “We’re masters of manipulation,” the article announces. “We love getting into contestants’ heads on camera” (because via the “confessional” interviews so common on reality shows, “you can nudge a cast member to think a certain way”). Here’s one more “secret” revealed by those anonymous authors of reality: “We’re all-powerful.”

Late in the first season of Survivor, the 2000 CBS show whose smash success set the template for reality TV as a genre, Kelly Wiglesworth, a river guide from Las Vegas, wins one of the show’s challenges. Her reward for the victory is first to be whisked away from the camp that she and her fellow contestants have built on a beach near Borneo. But that’s not all: She gets to spend her reprieve with Survivor’s host, Jeff Probst, drinking beer—Bud Light, Probst mentions aloud—and watching … the premiere of Survivor. The scene that results, set in a “bar” that has been constructed for the stunt, is both an artifact of the early days of reality TV and a harbinger of the cheerful self-referentiality that American pop culture would adopt in the early 21st century: There was Wiglesworth, situated beneath a neon sign that read SURVIVOR BAR, laughing with recognition as she saw herself being stranded (“stranded”) with her fellow castaways (“castaways”) in the South China Sea. There she was, sipping her product-placed beer, watching herself being watched.

Survivor is now 20 years old; the pilot episode that Wiglesworth viewed with Probst aired in May of 2000. The show, currently airing its 40th(!) season, stays true, still, to the structure it debuted after Mark Burnett pitched it as an Americanized version of the Swedish show Expedition: Robinson—reality TV as a war of attrition. The contestants’ ultimate goal, Probst often told viewers that first season, with no apparent abashment, was to outlive the 15 other voluntary castaways to become the show’s “sole survivor.” To accomplish that—and, thus, to win the show’s prizes ($1 million and, for good measure, a Pontiac Aztek)—the players would be required to subject themselves to an array of manufactured hardships. And they would need to accommodate themselves to the demands outlined in the show’s motto: “Outwit. Outplay. Outlast.”

The game show had epic overtones. Each episode of Survivor’s pilot season made a point of reiterating the great danger the contestants had put themselves in as they battled for survival. (As evidence of the threat, the show offers a lot of B-roll of snakes—some of them striking out, menacingly, in the direction of the camera.) Each episode, as well, professes a great interest in ethics. Tribal Council, the recurring meeting during which contestants vote one another off the show, is also the time when, as Probst repeatedly intones, you “account for your actions” on the island. He adds, at one point: “What happens here is sacred.”

Against that backdrop of moral reckoning, though, there is also “tree mail,” the quirky mechanism through which the show’s producers communicate with contestants, informing them of the challenges they will be required to participate in to win immunity or other rewards. (The messages, for reasons left unexplained by a show that is set in the 21st century, are often written in old-timey script—and in rhyming couplets.) There are also “immunity idols”: the statues whose possession confers protection from elimination. There is the fact that Tribal Council often takes place on sets whose decor (rickety rope bridges, torches, fire pits that double as amphitheaters) is less evocative of Lord of the Flies than of Legends of the Hidden Temple. Before casting their votes for who should be banished from the island, contestants discuss the events of the past several days while gathered around the pit in the manner of sitcom characters at a dinner table: arranged in a neat semicircle so that each face is exposed to the camera. In the foreground of the Tribal Council scene, over several episodes in the first season, sits a treasure chest whose wide maw is open to reveal stacks of play money.

That campy aesthetic is telling: The concept of the show as a high-minded, man-versus-man-versus-nature saga is attenuated by the knowingly manufactured elements of the game. Survivor’s producers are its minor gods. Why did that first episode feature 16 contestants? Why were those contestants divided into two tribes? Why were they required to complete the particular challenges presented to them? Because offstage power brokers—Burnett and his fellow producers—made those decisions on their behalf. Those agents are rarely acknowledged on the show, but their desires and demands are total. The contestants and, consequently, the viewers navigate the world they’ve constructed.

Unseen forces bending the arc of human lives: This is also, as it happens, a foundational assumption of any conspiracy theory. (One of Survivor’s fellow long-running reality shows is named Big Brother; the title is a revealing joke.) One of Hofstadter’s arguments in The Paranoid Style is that the conspiracy-minded tend to see history itself as the outcome of malicious powers—secretive, collective, nebulous—wantonly executing their will. All the world as Oz, with invisible wizards pulling the strings; this idea is cheerfully validated every Wednesday at 8 p.m. (7 p.m. Central). Joseph Uscinski, a political-science professor at the University of Miami and a co-author of the book American Conspiracy Theories, notes how readily the internal logic of shows like Survivor can echo the power dynamics of conspiracist thought. Contestants might say, “It’s beyond our control,” he told me recently of the experiences those shows create. As for the relationship those contestants have with the shows’ producers: “We’re at their whim.”

In some ways, that also describes the transactions of fiction: Authors create, and audiences are willful captives of the creation. But the terms of fiction, which have been negotiated over centuries, are widely established and commonly understood. They have a luxury that an extremely young genre does not. Survivor’s first episode aired two years after the release of The Truman Show, a film that neatly illustrates the anxieties that would attend the age of reality TV. Truman Burbank (played by Jim Carrey) is an orphan adopted by a studio as a newborn so that his life could be aired as a television show. As an unwitting—and, thus, unwilling—reality star, Truman is also the embodiment of an idea that might be paranoid were it not, in his case, true: The whole world is conspiring to dupe him. Truman’s mother and father and wife and best friend are actors who pretend to love him. His blandly idyllic home, his profession, his marriage—the very weather he moves in—are guided by distant producers who utter directives like “Cue the sun.”

The movie, whose plot is propelled by Truman’s slow realization that his life has been one of surveillance, is a satire informed by several other genres (“Comedy, Drama, Sci-Fi,” one review classified it). Often, though, the film reads most readily as horror. Truman is trapped, utterly. He is controlled, thoroughly. TV viewers—reminders of how possible it is to be obsessed with celebrities without fully caring about them—are the monsters that pursue him. But the real villain of the film is The Truman Show’s “designer and architect,” Christof (Ed Harris), who controls cameras with the verve of a maestro and who justifies his manipulations by telling a journalist, “We accept the reality of the world with which we’re presented. It’s as simple as that.”

This is the paranoid style, reimagined as fiction. And it extends into the nascent phenomenon that The Truman Show is satirizing. “I can’t tell what’s real and what’s fake,” a contestant on the current season of Survivor, frustrated by the show’s latest round of machinations, whispers to a fellow competitor. Another contestant patiently explains his strategy to the cameras: “What I have to do is pretend that I’m on a side that I’m really not ... I’m undercover so I can keep infiltrated in the group that I really want out.”

Double-dealing. Mutualized suspicion. Paranoia that is serially justified. Survivor, over its two-decade run, has concocted many methods of complicating its premise, including bringing back fan favorites and villains and finding new ways to pit tribes against one another. (Remember Brawn vs. Brains vs. Beauty?) Survivor recently introduced a new way for contestants to “outwit” one another; it dubbed this mechanism the “Extortion Advantage.” The game has gotten rougher, the production values sleeker; but the ideas that animated the first season have remained. Survivor, through it all, has treated its own project as a slow and sweeping metaphor—for Darwinism, for capitalism, for America, for life itself.

Before the final vote that first season—before several contestants who had been voted off the island were asked to choose whether Richard Hatch, the communications strategist who was presented as an avatar of American corporatism, or Wiglesworth, the yoga-posing nature guide, would win the show’s prizes—Probst delivered a speech. Over the previous 39 days, he told the contestants, “you’ve created a new civilization and you lived within it, and you all played the game very well—a game that definitely parallels our own regular lives in ways that we probably never imagined.” This was an echo of how Burnett, who counts Lord of the Flies as a favorite book, had sold the show: as an exploration, one report summed up, of “how real people relate to each other under pressure”—one “that might even say something profound about the human condition.”

That “real people” premise, though, gets stretched when you notice that, on the buffs the contestants wear to signal their tribal affiliation, the Survivor logo is printed next to another one: Reebok. The premise gets stretched thinner still when, for one of the challenges, Probst distributes handheld camcorders to contestants and sends them into the jungle to film what he calls The Survivor Witch Project. (The Blair Witch Project, a film that had its own fun putting scare quotes around reality, had premiered in 1999.) The premise gets stretched thinner still when, from under the stained pants and tattered tank tops that present Survivor as a sober study of communal abjection, mic packs peek out. In 2001, just after Survivor had become a hit, ABC News ran an article that anticipated BuzzFeed’s “17 Secrets About Reality TV Shows That’ll Make You Question Everything.” Headlined “Some Survivor Scenes Were Reenactments,” the piece reports that Burnett “admitted this week he sometimes reenacts scenes of his hit CBS show to get a more picturesque shot.” The story notes Burnett’s insistence that the reenactments served merely aesthetic purposes—and that the contestants’ behavior itself was spontaneous. It adds: “But he said he sees no reason why ‘reality’ should stand in the way of production values.”

Peter Knight, the author of the 2000 book Conspiracy Culture: From the Kennedy Assassination to The X-Files, studies the intersection of conspiracy theory and American popular culture. And many TV shows, he told me, “are basically ways for American society to stage political philosophy debates that it might find hard to do in other ways.” Neoliberalism versus collectivism, dog-eat-dog politics versus acting for the good of the pack—Survivor, Knight noted, is a loaded show that comes down to a loaded question: “Does altruism get you the prize or does paranoia get you the prize?”

That tension helps explain Survivor’s Machiavellian tilt—and its decades-long appeal. One of P. T. Barnum’s insights into the success of his various hoaxes was that people, on some deep level, love being fooled. They enjoy it so much, in fact, that they will happily pay for the privilege of being lied to—because the lie itself becomes a puzzle to be solved. Survivor, a show created by a man who operates in the Barnumian tradition, leverages a similar recognition. The allure of reality TV is not merely voyeurism, but also the cathartic thrill of suspicion. As Nancy L. Rosenblum and Russell Muirhead argue in their 2019 book, A Lot of People Are Saying: The New Conspiracism and the Assault on Democracy, disorientation—the cognitive chaos of “conspiracy without the theory”—is an element of the latest form of American conspiracism. So is knowingness: the electric rush of feeling savvy to the workings of the world in a way most people are not.

The shows that Survivor helped inspire typically argue the same. Every contestant on The Bachelor who whispers that her competition isn’t “there for the right reasons,” every person who is edited to be a hero or a villain, every real-estate agent who flips a house, every diva who flips a table—each dares viewers to consider what’s real, what’s fake, and what’s the difference. So do the tabloids, the places where the casts of the shows go to tell their “true stories” in more detail. So do satires like UnREAL—a darkly fictionalized treatment of the behind-the-scenes workings of a Bachelor-like dating show. For the audience, part of the satisfaction of it all is in the sleuthing: fan fiction, in reverse. The X-Files, its premise inspired by extremely nonfictional failures of the American government, employed this imperative as one of its taglines: “Trust no one.” This, however, was another of the show’s mottos: “The truth is out there.”

Viewers, in general, know they are being duped. But once you see the duplicity, it becomes easy to notice its outlines everywhere: in other entertainments, in the news media, in world events. Who are the producers editing the news programs that, in turn, edit the world? Who are the producers working behind the scenes of the American university, or of American government, or of American history? Who has power? Who should? The CBS executive to whom Mark Burnett pitched Survivor was Leslie Moonves, who—though he denied the allegations—would later resign from the network after a series of sexual-assault claims against him were brought to light. Burnett would tweak the premises of his smash hit to create The Apprentice, the series that laundered Donald Trump’s reputation so efficiently that it helped him win the American presidency. Producers of The Apprentice have given interviews detailing the ways they edited their footage of Trump to make him seem more coherent, more intelligent, more authoritative. The conceit of their show would make sense only with a successful mogul as its star. So the producers created one. “Most of us knew he was a fake,” one of them said in 2018. “He had just gone through I don’t know how many bankruptcies. But we made him out to be the most important person in the world. It was like making the court jester the king.”

The rest of us are living with the consequences. Trump, elevated by television, treats his presidency as an outgrowth of the medium. He preens through his duties as if he were still on a set, his face soft-lit, his mistakes studiously back-edited. But those performances, of course, are all too real. The people on the other end of them—many fearing what might become of their lives with each new season of Trump’s America—have little recourse but to watch as the show goes on. Casts and viewers, plots and twists—what is the rational reading of this irrational moment in human history? What is the conspiratorial one? The show itself will not answer. The star will do what he does. But the producers might whisper, from behind the scenes, what so many of them know to be true: With enough footage, you can turn anything into reality.