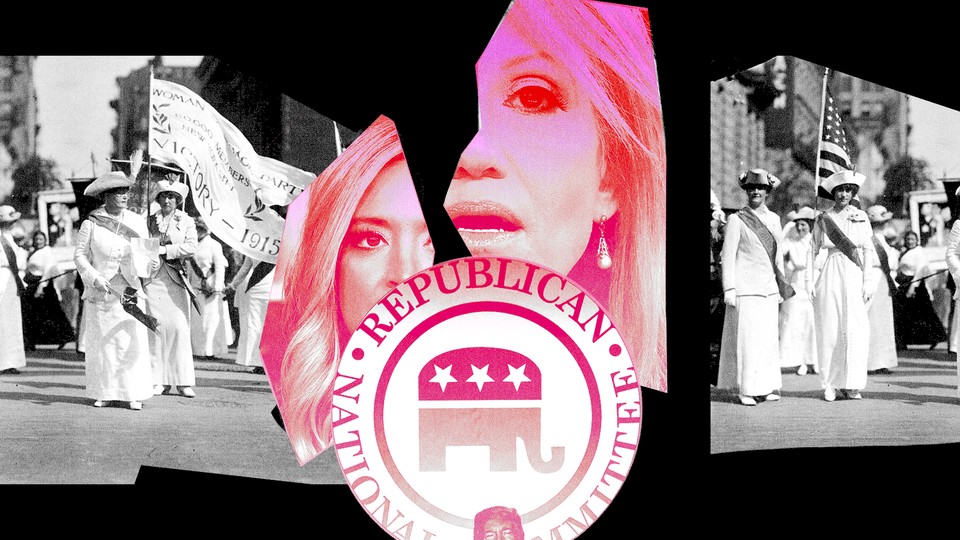

The RNC Is Terrified of Losing Women Voters

GOP leaders sold a female-friendly version of Donald Trump at the convention, despite dark parts of the president’s history.

President Donald Trump is in trouble with women voters, and the GOP knows it. At the Republican National Convention last night, everyone from Vice President Mike Pence to Trump’s departing counselor, Kellyanne Conway, eagerly pointed out that they were speaking on the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Nineteenth Amendment, which granted women the right to vote. Trump’s daughter-in-law, Lara, praised the president’s mentorship of women in senior administration roles, and his press secretary, Kayleigh McEnany, testified to his solicitude after her preventative double mastectomy. The intended message was clear: Trump is a man who supports women, no matter what you may have once heard him say on a hot mic. But will Americans buy it?

Recent polling suggests that most women do not intend to vote for Trump this November. Former Vice President Joe Biden leads Trump among registered women voters by 21 percentage points, according to an August poll from The Wall Street Journal and NBC News, a gap consistently found in surveys taken throughout the summer. GOP officials have apparently been watching these numbers with alarm—especially the women who work in the White House. “Trump has been hemorrhaging women overall for a while,” Tara Setmayer, a former Republican congressional communications director, told me in a text message. “Kellyanne is a pollster by trade so she knows this demo better than anyone. The messaging to women tonight is intentional, without question.”

Women voters may determine who wins the 2020 election: They turn out to vote in higher numbers than men, and they are an influential constituency in the suburban districts where Trump stands to lose badly among 2016 supporters. With Trump perpetually trailed by allegations of sexual assault, the RNC is attempting to brand the president as the kind of leader the suffragettes would have admired.

Last night’s lineup was dominated by images of historical women activists marching in the streets and protesting at ballot boxes. Lara Trump narrated a GOP-flavored history of women’s suffrage, theatrically emphasizing that suffragists launched their efforts over a tea party, a nod to the 2010s-era anti-government movement, and noting that leaders such as Susan B. Anthony exclusively supported Republican candidates for office. Even 100 years after the Nineteenth Amendment, “a woman in a leadership role can still seem novel,” Conway said, noting that she’d broken a barrier in politics as the first woman to lead a winning presidential campaign. “Not so for President Trump. For decades, he has elevated women to senior positions in business and in government. He confides in and consults us, respects our opinions, and insists that we are on equal footing with the men.” Democrats have often claimed the legacy of women’s-suffrage activism for themselves, but Conway and McEnany wore suffragette white.

The night’s speakers pitched a GOP-friendly version of feminism—a vision focused on balancing motherhood and careers, championing hard work, and not asking for what they described as special privileges based on gender.

“For many of us, women’s empowerment is not a slogan,” Conway said. “It comes not from strangers on social media, or sanitized language in a corporate handbook. It comes from the everyday heroes who nurture us, shape us, and who believe in us.” Lara Trump described the “countless women executives” she encountered who worked for Trump. “Gender didn’t matter,” she said. “What mattered was the ability to get the job done.” And McEnany talked about Trump’s encouragement of her as the working mother of a newborn. “I choose to work for this president, for her,” she said, in reference to her daughter.

The first three nights of the RNC also highlighted President Trump’s ostensible support for racial equality, including a segment in which he pardoned a Black man convicted of committing bank robbery. This message of an inclusive, kinder GOP is arguably pitched not only at minority voters, but also at suburban women who are reluctant to vote for Trump “because they feel that he is racist, too racist, in a way that they can’t personally affiliate with him,” Liz Mair, who worked as a communications adviser to Republican political candidates, told me in a text. “If they succeed enough with a lot of their ‘we’re not actually racist’ programming, that should help them with suburban women voters.”

Conventions are as much about a party’s anxieties as they are about that party’s vision for America—the themes that are emphasized most strongly often reveal where the party sees its vulnerabilities. If last night’s unending suffragette talk is any indication, Republicans are extremely nervous that women are not sold on a second Trump term. But a little revisionist history may not be enough to swing women at the polls in November. They already know a different version of Trump.